Article: The Suffering Children of Enduring Conflicts

Tooba Khurshid

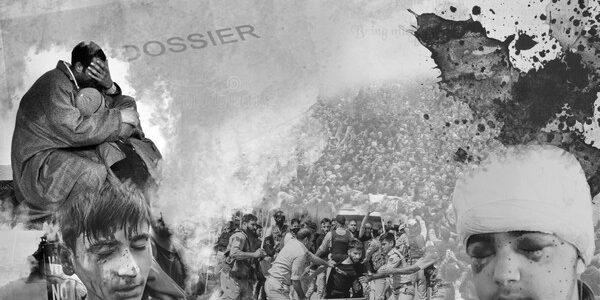

Conflicts have a devastating impact on children’s well-being across the world. An estimated 420 million children today, live in conflict zones including the Middle East, Kashmir, and South Sudan. They continue to suffer extreme violence and abuse. Perpetrators of violence are committing atrocities with impunity which puts the lives of millions of children at risk.

Generations of Kashmiris have known nothing but violence, detentions, killings, imprisonments, displacements, rape and abuse. The impact of such an environment is profound and shapes lifetime attitudes. Children in Kashmir have also come under direct attacks of such abuses. Their schools and homes are bombed, their families are tortured and killed, which impinges on their physical and mental health.

The Kashmiri children have been heavily affected by the presence of Indian occupation forces which has deeply impacted them, their entire lives as well as impeded their development. The structural changes in the society have immensely obstructed their values and they have entirely lost sense of security and peace of mind.

Having grown up amidst the cycle of violence, today they are trapped by the horrors of violence that have left them traumatized and bereaved. For children across Kashmir, encounters with the Indian occupation forces and settlers have become a routine. Living under the heavy blockades and extreme economic hardships, they are amongst those who have been hit the hardest. Ever since the revocation of Article 370, the children of Kashmir have been beaten up and tortured in custody, leaving them scared and their families helpless. In 2019 only, Indian occupation forces detained 144 minors under the Public Safety Act (PSA) and Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) for ‘protesting against the Indian decision.’ Self-accounts of some of the children who were released testified abuse and torture.

Article (7) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) prohibits torture. Article 37 (a) of Convention on the Rights of the Child specifically obliges states to ensure that “No child shall be subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

Living in the world’s most militarized zone, they have become the easiest target of repression and brutality. The presence of permanent occupation forces in the surroundings leads to psychological impact on the children and they feel under constant threat and anxiety. The persistent threat of harm intensifies exposure to psychological trauma including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, behavioral issues, among other issues. Such toxic stress impairs the children’s capacity to engage in daily life.

According to the Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences Kashmir (IMHANS-K), it has seen around 200 mental trauma cases among children in the year 2020, marred by repeated crackdowns, encounters, tortures, detentions and killings in Kashmir. According to their statistics “around 80% of the affected children belonged to pre-adolescence and early adolescence age groups. Most children identified the presence of forces as a trigger for anxiety, petulance, and anger. Many were having flashbacks, inducing episodic sightings of trauma, fright, scary dreams, and sleep disorders.”

In such circumstances, schools are the places that act as counsellors and help children to overcome their psychological trauma. Sadly, indiscriminate shelling by occupation forces across the Line of Control (LoC) has caused huge damages to the schools instigating major disruptions in education and has worsened the safe space for children. Heightened fear and distress had led to the closure of hundreds of schools across the LoC before revival of the 2003 ceasefire agreement by two sides. At least 1.5 million Kashmiri children remain out of school. Destruction, constant disruption and violence have hugely affected the children’s intellectual development and mental health.

A 2018 study ‘Prevalence of Childhood Mental Disorders Among School Children of Kashmir Valley’ from Community Mental Health Journal uncovered the ratio of schoolgoing children with mental disorders in the valley stating, “The most commonly found mental disorders were of anxiety (8.5 percent), followed by mood disorders (6.3 percent) and then behavioral disorders (4.3 percent).”

Rampant use of weapons like cluster munitions and shotguns make no distinction between adults and children. Use of shotguns time and again has caused thousands of injuries and blinded hundreds. According to the Human Rights Watch, from July 2016 to February 2019, 6221 people were injured by shotguns, 139 were blinded and 782 had eye injuries including children. The youngest pellet victim in Kashmir was 18-month-old Hiba Nasir who was struck inside her house by the Indian occupation forces. Article 3 of Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials (1979) clearly states that: “Law enforcement officials may use force only when strictly [reasonably] necessary and to the extent required for the performance of their duty.” Furthermore, Special Provisions of the Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials (1990) set basic principles for the use of arms and non-lethal weapons and states that: “In any event, intentional lethal use of firearms may only be made when strictly unavoidable in order to protect life.” Hence such or any weapons can thus only be used if there is grave danger of death or injury that cannot be averted otherwise. This brings into question the harm an 18-month-old would have possibly inflicted to the occupation forces that pushed them to hit her to the extent that her life was endangered. Article 6 (1) of ICCPR declares and compels that “Every human being has the inherent right to life. This right shall be protected by law. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life.”

Exposed to all kinds of violations and sense of injustice, many children have to live with shattered families. Profound loss of a parent(s) or family member(s) and separation in childhood increases their hardships. The absence of peace and spectre of violence has caused depression leading to anorexia nervosa (an eating disorder) and phobic anxiety.

While surviving the life-threatening and life-altering dangers of the conflict, the COVID-19 pandemic added further to their anxieties and hardships in their daily lives. As the second wave hit Kashmir, cases of the acute virus are steadily increasing among children and a significant number of children show asymptotic or non-specific symptoms. On the one hand, they had devastating and lifelong effects of the conflict, and on the other, they are facing protection risks from the pandemic. According to the reports, children are at a high risk of developing Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome of Children (MIS-C) which is a syndrome similar to Kawasaki disease and toxic shock syndrome. International humanitarian law under exceptional circumstances like the pandemic, allows restrictions of certain human rights for public protection but while ensuring access to basic necessities and health services. In Kashmir, people witnessed the largest security and communications lockdown from 2019-20 and COVID-19 restrictions added to ‘a lockdown within the lockdown.’ Hence, an already collapsing healthcare system and the rise of contagious delta variant signalled a major health crisis. Poor health systems in Kashmir are unable to meet the existing health conditions of the people and children who had earlier undergone traumatic conflict events and tortures are more vulnerable to the new stressors.

The underlying aspect of the Indian occupation is confrontations between the Indian Occupation Forces and unarmed civilian protestors. Since the abrogation of Article 370, these clashes intensified when India launched an all-means assault on the people including deaths and injuries under military-enforced curfew. A crucial aspect of this havoc is the ‘culture of impunity’ surrounding those who deliberately hurt or fail to protect children. United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres conveyed apprehensions over the child casualties and torture in Kashmir and urged India “to take preventive measures to protect children, including by ending the use of pellets against children.” Yet the perpetrators of these abuses rarely face justice and fear of trials.

The extent, intensity, and impact of the violence inflicted upon children in Kashmir hints at systematic breaches of international civil and criminal law. On June 4, the world observed ‘International Day of Innocent Children Victims of Aggression.’ The day acknowledges the physical, mental and emotional pain endured by the children across the world. This day upholds the United Nation’s pledge to protect and promote children rights as guided by CRC. Nevertheless, India systematically violated the fundamental rights – which the Indian government is morally and legally obliged to provide to the children of Kashmir – with impunity.

Deliberate widespread targeting and failure to protect the civilians in Kashmir constitute war crimes under the 1907 Hague Regulations, the 1949 Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols, and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), together with customary international humanitarian law. CRC, of which India is a signatory, establishes the principle that children have the right to protection from all kinds of physical or mental aggression, harm, and abuse. Despite that, against the letter and spirit of international law, India continues to violate all the provisions.

So, the question arises why?

When it comes to the rights of Kashmiris and Kashmiri children, human rights are often seen as a two-tier standard. The Indian acts and aggression are condemned yet these actions are followed by increased military assistance. Such two-tier standards are weakening the human rights standards and provide a very thin line of defense. The children of Kashmir have the right to expect better justice and accountability from the international community. Apart from humanitarian ceasefire demands, international community should declare Indian violence against the children as felonious and intolerable. To promote international human rights law and guarantee accountability for violations perpetrated against children, a lot more needs to be done.

Sustainable Development Agenda 2030 provides a comprehensive universal plan to transform the world and secure a better future for the children. The agenda for the first time emphasized on “ending abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children.” The agenda gave a new momentum for the realization of rights of children to live free from violence and abuse. International children’s rights and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) reinforce each other. According to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, “the realization of children’s rights is the foundation for securing a sustainable future and realizing all human rights.” Hence for preventing children at risk, SDGs need to be implemented in accordance with international children rights.

The evaluation and screening of mental health issues for the population affected by conflicts is generally difficult. In the case of Kashmir, where communication blackout and lockdowns are rampant, the access of information and services is a challenge. Research on children’s mental health under occupation, especially in Kashmir, has not been a priority, therefore, the research targeting children who need it the most is lacking. There is a dire need to prioritize and establish mechanisms to assess and support the needs in Kashmir.

A combined universal integrated approach is required to compel India for the implementation of mechanisms for the protection of children rights. To uphold international laws and standards, the restrictions that avert basic necessities of life and healthcare shall be removed. Keeping in view the harms and causalities of children in Kashmir, strong monitoring and mechanisms are required to hold the violators accountable.

The writer is an expert on international law and human rights with a special focus on South Asia and Kashmir. She is the Editor of Asian Journal of Law and Society, Cambridge University Press.

Article: The Suffering Children of Enduring Conflicts

Tooba Khurshid

Conflicts have a devastating impact on children’s well-being across the world. An estimated 420 million children today, live in conflict zones including the Middle East, Kashmir, and South Sudan. They continue to suffer extreme violence and abuse. Perpetrators of violence are committing atrocities with impunity which puts the lives of millions of children at risk.

Generations of Kashmiris have known nothing but violence, detentions, killings, imprisonments, displacements, rape and abuse. The impact of such an environment is profound and shapes lifetime attitudes. Children in Kashmir have also come under direct attacks of such abuses. Their schools and homes are bombed, their families are tortured and killed, which impinges on their physical and mental health.

The Kashmiri children have been heavily affected by the presence of Indian occupation forces which has deeply impacted them, their entire lives as well as impeded their development. The structural changes in the society have immensely obstructed their values and they have entirely lost sense of security and peace of mind.

Having grown up amidst the cycle of violence, today they are trapped by the horrors of violence that have left them traumatized and bereaved. For children across Kashmir, encounters with the Indian occupation forces and settlers have become a routine. Living under the heavy blockades and extreme economic hardships, they are amongst those who have been hit the hardest. Ever since the revocation of Article 370, the children of Kashmir have been beaten up and tortured in custody, leaving them scared and their families helpless. In 2019 only, Indian occupation forces detained 144 minors under the Public Safety Act (PSA) and Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) for ‘protesting against the Indian decision.’ Self-accounts of some of the children who were released testified abuse and torture.

Article (7) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) prohibits torture. Article 37 (a) of Convention on the Rights of the Child specifically obliges states to ensure that “No child shall be subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

Living in the world’s most militarized zone, they have become the easiest target of repression and brutality. The presence of permanent occupation forces in the surroundings leads to psychological impact on the children and they feel under constant threat and anxiety. The persistent threat of harm intensifies exposure to psychological trauma including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, behavioral issues, among other issues. Such toxic stress impairs the children’s capacity to engage in daily life.

According to the Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences Kashmir (IMHANS-K), it has seen around 200 mental trauma cases among children in the year 2020, marred by repeated crackdowns, encounters, tortures, detentions and killings in Kashmir. According to their statistics “around 80% of the affected children belonged to pre-adolescence and early adolescence age groups. Most children identified the presence of forces as a trigger for anxiety, petulance, and anger. Many were having flashbacks, inducing episodic sightings of trauma, fright, scary dreams, and sleep disorders.”

In such circumstances, schools are the places that act as counsellors and help children to overcome their psychological trauma. Sadly, indiscriminate shelling by occupation forces across the Line of Control (LoC) has caused huge damages to the schools instigating major disruptions in education and has worsened the safe space for children. Heightened fear and distress had led to the closure of hundreds of schools across the LoC before revival of the 2003 ceasefire agreement by two sides. At least 1.5 million Kashmiri children remain out of school. Destruction, constant disruption and violence have hugely affected the children’s intellectual development and mental health.

A 2018 study ‘Prevalence of Childhood Mental Disorders Among School Children of Kashmir Valley’ from Community Mental Health Journal uncovered the ratio of schoolgoing children with mental disorders in the valley stating, “The most commonly found mental disorders were of anxiety (8.5 percent), followed by mood disorders (6.3 percent) and then behavioral disorders (4.3 percent).”

Rampant use of weapons like cluster munitions and shotguns make no distinction between adults and children. Use of shotguns time and again has caused thousands of injuries and blinded hundreds. According to the Human Rights Watch, from July 2016 to February 2019, 6221 people were injured by shotguns, 139 were blinded and 782 had eye injuries including children. The youngest pellet victim in Kashmir was 18-month-old Hiba Nasir who was struck inside her house by the Indian occupation forces. Article 3 of Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials (1979) clearly states that: “Law enforcement officials may use force only when strictly [reasonably] necessary and to the extent required for the performance of their duty.” Furthermore, Special Provisions of the Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials (1990) set basic principles for the use of arms and non-lethal weapons and states that: “In any event, intentional lethal use of firearms may only be made when strictly unavoidable in order to protect life.” Hence such or any weapons can thus only be used if there is grave danger of death or injury that cannot be averted otherwise. This brings into question the harm an 18-month-old would have possibly inflicted to the occupation forces that pushed them to hit her to the extent that her life was endangered. Article 6 (1) of ICCPR declares and compels that “Every human being has the inherent right to life. This right shall be protected by law. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life.”

Exposed to all kinds of violations and sense of injustice, many children have to live with shattered families. Profound loss of a parent(s) or family member(s) and separation in childhood increases their hardships. The absence of peace and spectre of violence has caused depression leading to anorexia nervosa (an eating disorder) and phobic anxiety.

While surviving the life-threatening and life-altering dangers of the conflict, the COVID-19 pandemic added further to their anxieties and hardships in their daily lives. As the second wave hit Kashmir, cases of the acute virus are steadily increasing among children and a significant number of children show asymptotic or non-specific symptoms. On the one hand, they had devastating and lifelong effects of the conflict, and on the other, they are facing protection risks from the pandemic. According to the reports, children are at a high risk of developing Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome of Children (MIS-C) which is a syndrome similar to Kawasaki disease and toxic shock syndrome. International humanitarian law under exceptional circumstances like the pandemic, allows restrictions of certain human rights for public protection but while ensuring access to basic necessities and health services. In Kashmir, people witnessed the largest security and communications lockdown from 2019-20 and COVID-19 restrictions added to ‘a lockdown within the lockdown.’ Hence, an already collapsing healthcare system and the rise of contagious delta variant signalled a major health crisis. Poor health systems in Kashmir are unable to meet the existing health conditions of the people and children who had earlier undergone traumatic conflict events and tortures are more vulnerable to the new stressors.

The underlying aspect of the Indian occupation is confrontations between the Indian Occupation Forces and unarmed civilian protestors. Since the abrogation of Article 370, these clashes intensified when India launched an all-means assault on the people including deaths and injuries under military-enforced curfew. A crucial aspect of this havoc is the ‘culture of impunity’ surrounding those who deliberately hurt or fail to protect children. United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres conveyed apprehensions over the child casualties and torture in Kashmir and urged India “to take preventive measures to protect children, including by ending the use of pellets against children.” Yet the perpetrators of these abuses rarely face justice and fear of trials.

The extent, intensity, and impact of the violence inflicted upon children in Kashmir hints at systematic breaches of international civil and criminal law. On June 4, the world observed ‘International Day of Innocent Children Victims of Aggression.’ The day acknowledges the physical, mental and emotional pain endured by the children across the world. This day upholds the United Nation’s pledge to protect and promote children rights as guided by CRC. Nevertheless, India systematically violated the fundamental rights – which the Indian government is morally and legally obliged to provide to the children of Kashmir – with impunity.

Deliberate widespread targeting and failure to protect the civilians in Kashmir constitute war crimes under the 1907 Hague Regulations, the 1949 Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols, and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), together with customary international humanitarian law. CRC, of which India is a signatory, establishes the principle that children have the right to protection from all kinds of physical or mental aggression, harm, and abuse. Despite that, against the letter and spirit of international law, India continues to violate all the provisions.

So, the question arises why?

When it comes to the rights of Kashmiris and Kashmiri children, human rights are often seen as a two-tier standard. The Indian acts and aggression are condemned yet these actions are followed by increased military assistance. Such two-tier standards are weakening the human rights standards and provide a very thin line of defense. The children of Kashmir have the right to expect better justice and accountability from the international community. Apart from humanitarian ceasefire demands, international community should declare Indian violence against the children as felonious and intolerable. To promote international human rights law and guarantee accountability for violations perpetrated against children, a lot more needs to be done.

Sustainable Development Agenda 2030 provides a comprehensive universal plan to transform the world and secure a better future for the children. The agenda for the first time emphasized on “ending abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children.” The agenda gave a new momentum for the realization of rights of children to live free from violence and abuse. International children’s rights and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) reinforce each other. According to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, “the realization of children’s rights is the foundation for securing a sustainable future and realizing all human rights.” Hence for preventing children at risk, SDGs need to be implemented in accordance with international children rights.

The evaluation and screening of mental health issues for the population affected by conflicts is generally difficult. In the case of Kashmir, where communication blackout and lockdowns are rampant, the access of information and services is a challenge. Research on children’s mental health under occupation, especially in Kashmir, has not been a priority, therefore, the research targeting children who need it the most is lacking. There is a dire need to prioritize and establish mechanisms to assess and support the needs in Kashmir.

A combined universal integrated approach is required to compel India for the implementation of mechanisms for the protection of children rights. To uphold international laws and standards, the restrictions that avert basic necessities of life and healthcare shall be removed. Keeping in view the harms and causalities of children in Kashmir, strong monitoring and mechanisms are required to hold the violators accountable.

The writer is an expert on international law and human rights with a special focus on South Asia and Kashmir. She is the Editor of Asian Journal of Law and Society, Cambridge University Press.

- A tribute to the Resilience of Kashmiri Women - March 8, 2024

- Cycle Rally in Islamabad to show solidarity with people of Kashmir. - February 4, 2024

- 5th February, Kashmir Solidarity Day - February 4, 2024

Comment Here